Underwater photography. For some, it’s cheese rolling, bungee jumping or lawnmower racing. I get my kicks going beneath the waves to take photos and it’s possibly the craziest thing I’ve ever done…especially at night, which is surreal – and even more exciting.

It can be breathtakingly beautiful beneath the waves. Drifting at neutral buoyancy through stunning scenery in a state of relaxed calm is a wonderful, joyous experience. It can feel like flying. As a child growing up in the sixties with the moon shot program, I wanted to be an astronaut – lots of children did. This comes closest to the feeling of being in outer space, I think.

Me – Somewhere in the waters of the Surin Islands, Thailand.

Cameras and other electronics don’t like water so this activity is not just personally hazardous. You’re putting expensive electronic equipment in a box then subjecting it to extreme pressure in the ocean. If it goes well, it doesn’t leak, get steamed up, attacked (yes), lost or undergo some other misadventure – you’ve got away with it. Afterwards, it needs all the loving care of a newborn; every last trace of corrosive saltwater and grains of sand must be removed, all parts dried, batteries recharged, all O-rings greased and put somewhere safe while you go and check the rest of your dive equipment.

Magnificent Anemone – This looked grey until lit by a strobe.

I took these shots with a compact Canon S120 in an Ikelite housing with one Inon strobe. I have a screw-on close-up filter for macro and also a wide angle lens that can be attached while underwater. There is a limited range of controls when using this equipment compared to that of my Canon 5D IV so it’s a case of getting the best results with the equipment you have. The prescription dive mask I use doesn’t have the clarity of my usual specs and I can’t fine tune the focus so the results are hit and miss.

On my last trip, it took two weeks before I could get the camera to work at all under pressure. It was fine on the surface but not a depth. I won’t go into details but I went through a process of eliminating every possibility until I found an almost invisible 1mm grub screw needed tightening.

Green Turtle, Gili Isles, Indonesia.

The rules for producing interesting, successful images are the same whether above or below the water surface – locate a good subject, take care that the background doesn’t detract from but enhances the subject, use great lighting, compose the scene well etc. etc.

Finding an interesting subject is probably one of the easier things to accomplish underwater… Everything else is harder!

A Shoal of Unicorn fish.

Diving is a potentially dangerous activity so it’s important to dive within strict safety parameters. This is not just for self-preservation but also that of your dive buddy and others in your dive group who, by the way, won’t wait for you. Going deeper than you’re equipped and trained for, losing your buddy, running out of air and damaging coral or wildlife are no no’s. It’s more likely for any of these things to happen when you’re focused on your subject and oblivious to your surroundings or dive computer.

Peacock Mantis shrimp with eggs. – This voracious predator can smash your housing with one strike. It has a “punch” of over 50 miles per hour (80 km/h) which is the fastest recorded punch of any living animal. The acceleration is similar to that in a .22 calibre handgun and can slice human fingers to the bone.

Well-camouflaged scorpionfish

Add to that the fact that you’re in a moving body of water, trying to stay completely still is nearly impossible. You could lie on the sand to stabilise yourself but watch out for hidden dangers just beneath the surface such as stingrays, stonefish and other potentially lethal creatures that won’t take kindly to being landing on. Well-camouflaged predators like this scorpionfish are easy to overlook and coral, for all its fragile beauty, cuts like a razor.

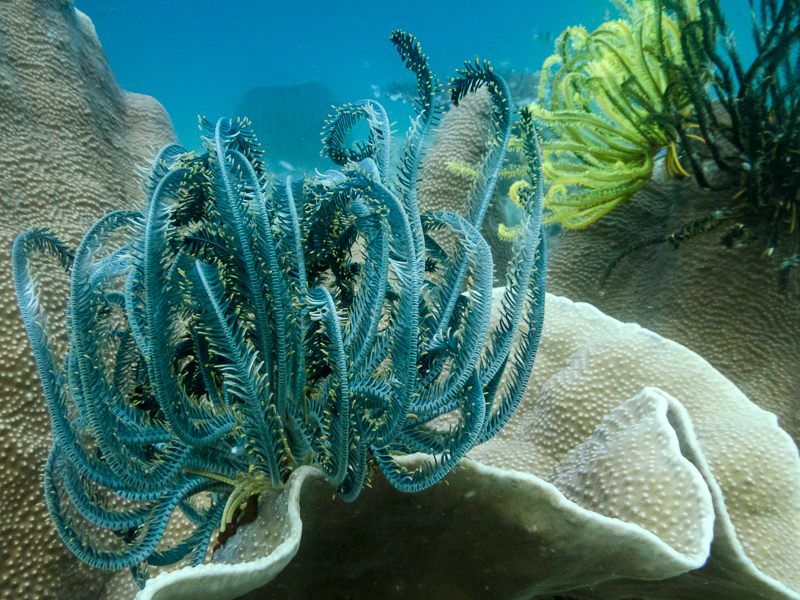

Feather stars on plates of foliate Turbinaria mesenterina coral.

Anemone, Lembeh Strait.

For all the difficulties, it’s exciting and seriously addictive. Only five percent of the oceans have been explored. Being in an alien world, seeing the most extraordinary things that I can’t believe are real, never knowing what I’ll find next, spur me on to find more. There are plenty of things that haven’t been identified yet. Perhaps the main reason for this is that the plant or creature has to be photographed on two different occasions and not have been identified previously. This is difficult to achieve but worldwide, 15-20,000 new species a year do get named and added.

Giant Frogfish inside a sponge.

Spinecheek anemonefish, male and female.

Radiant sea urchin.